This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

To Live Well is to Live Concealed

When the organ in the Trinity Church was restored in 1931, an old marble tablet was found under the large instrument. Five years later, the marble tablet was placed in the Round Tower’s Spiral Ramp, since marble tablets are not intended to be put away. Or said differently: it is not aimed at them when the old maxim states that to live well is to live concealed.

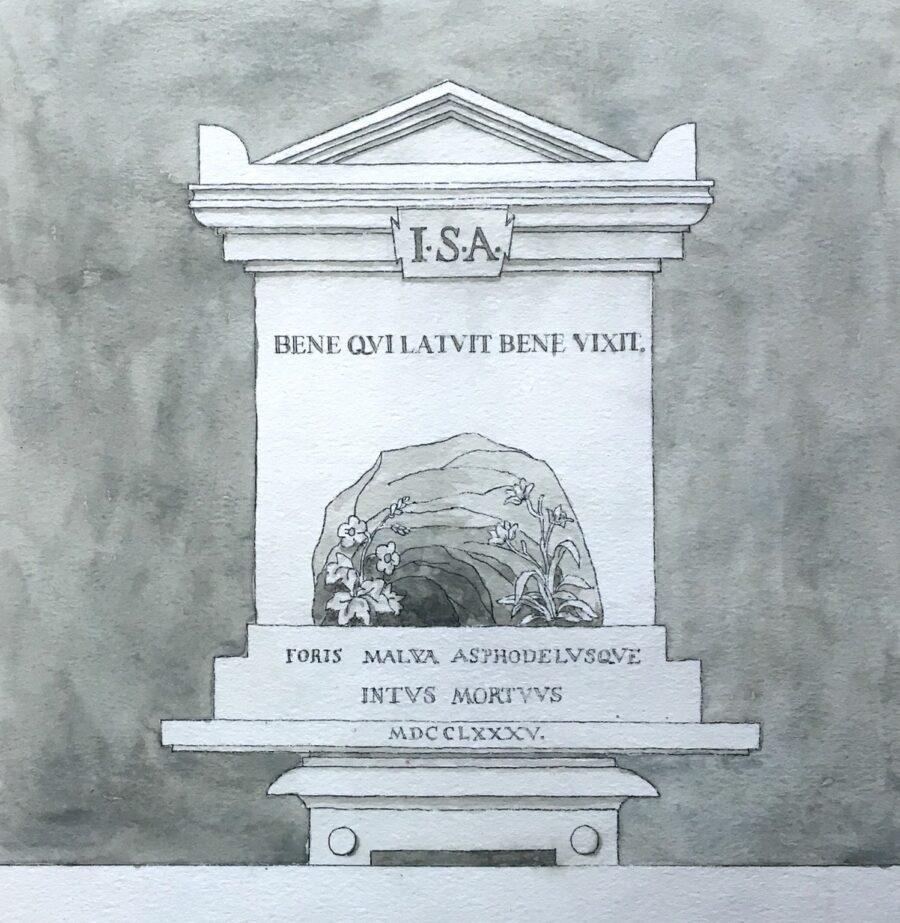

The words, most famously coined by the Roman poet Ovid, apply much better to one of the lesser-known astronomical writers of the 18th century, Johan Samuel Augustin (1715-1785). At least he believed so himself, for the maxim was his motto and was also written on his grave.

“But worse yet, the bodies emitted a stench that was both unpleasant and posed a health risk in the densely populated capital”

However, he did not manage to stay completely under the radar. Although it is not mentioned on the marble tablet in the Spiral Ramp, it was he, for instance, who wrote its Latin text. When his name is remembered by posterity, though, it has more to do with his final resting place than with his life.

Unhealthy Stench

When Johan Samuel Augustin, who was born in the Duchy of Schleswig but ended his days in Copenhagen, died in 1785, people who had the opportunity still preferred to be buried within the city’s ramparts and, most preferably, inside the churches that were considered to contain the most distinguished burial places.

According to the contemporary writer Rasmus Nyerup (1759-1829), though, the interments in the churches contradicted the very purpose of memorials. As he writes, “They deserve the name funeral monuments in a double respect as they are both monuments that are buried and hidden in nooks, and they also bury and extinguish the memory of the dead, which they should serve to maintain.” But worse yet, the bodies emitted a stench that was both unpleasant and posed a health risk in the densely populated capital. Or again in Nyerup’s words: “The air is poisoned by the rising mephitic vapours of the many interred corpses”.

Under the Open Sky

In 1760, to settle the problem a cemetery had been established outside the ramparts to relieve the churchyards of the city. It was difficult, however, to get posh Copenhageners to use the new Assistens Cemetery, literally the “assisting cemetery”, which was used for a long time only by the city’s less moneyed people.

Things did not get moving until Augustin made the unusual decision that he wanted be buried “auf dem Armen-Kirchhofe vor dem Norderthor” (“in the cemetery for the poor outside of Nørreport”), which he wrote in a supplement to his will a few months before his death. Nyerup summarizes his last will this way, “On the breadth of the grave his blameless spirit gave the testimony that he had never offended anyone while alive; now he did not want, after death, to poison the air that the survivors had to breathe in; he wanted to rest under the open sky.”

A Popular Cemetery

Augustin became “the first man of any reputation and elevated position in the state” buried at the Assistens Cemetery but was quickly followed by many others, also because of a 1805 ban to establish new indoor burial places.

One of those who was to be interred in the former cemetery for the poor was one of most important Danish sculptors of the 18th century, Johannes Wiedewelt (1731-1802). He was also behind several monuments in the cemetery, including the one commemorating Augustin, who had been his friend for many years. Wiedewelt’s monument for Augustin was located in the cemetery wall but has since disappeared and been replaced by a new one.

Thorough Work

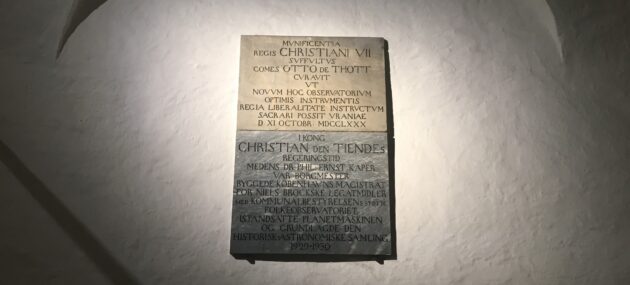

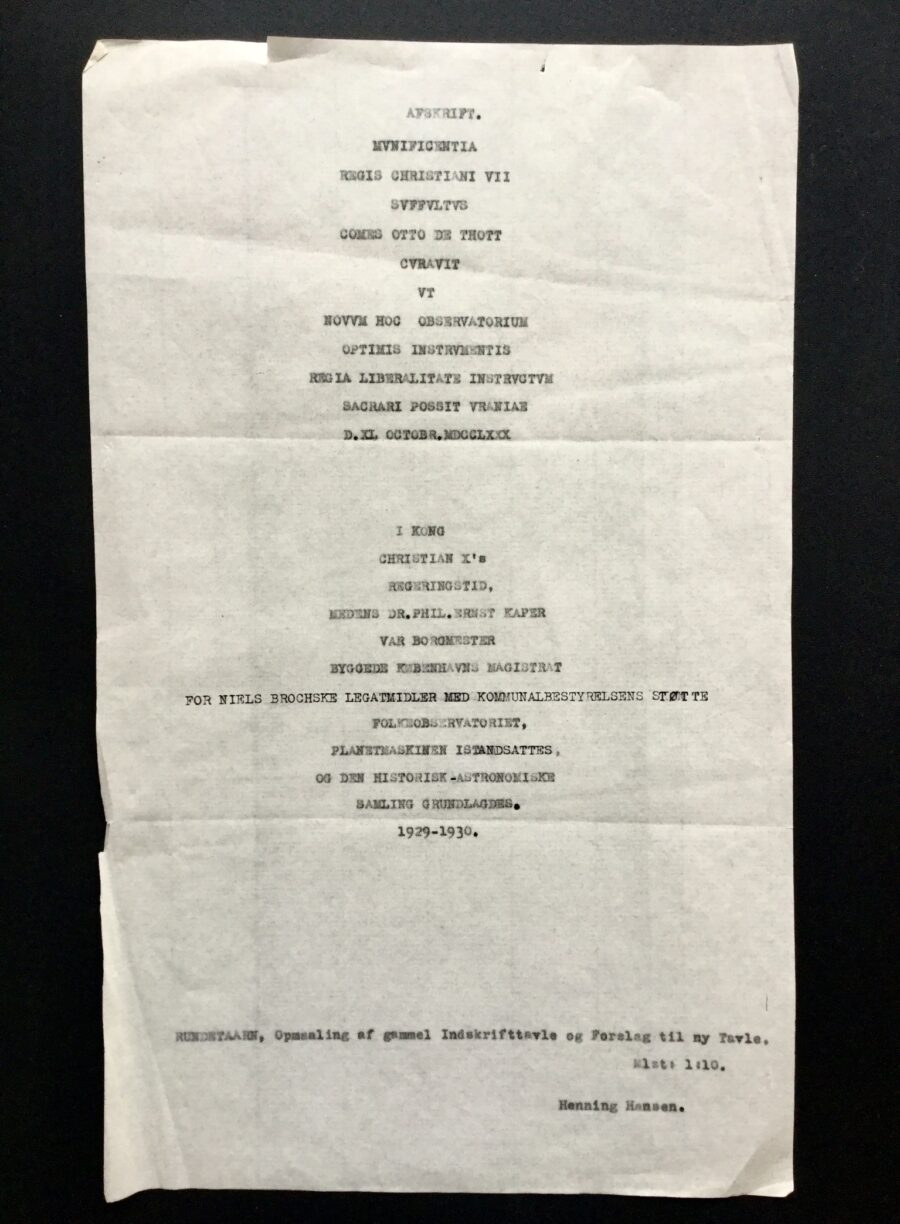

The marble tablet in the Round Tower’s Spiral Ramp, not one of Wiedewelt’s most prominent works but incidentally also carved by him, has been more fortunate. In the course of time, it has just lost the gilt of its letters apart from being moved. Commemorating the inauguration of a new observatory building from the late 18th century, the tablet was originally located above the entrance to the Observatory at the top of the Round Tower. After the Horrebow family had been in charge of the Observatory for much of a century, it needed a radical renewal, and the new leader, Thomas Bugge (1740-1815), proceeded with thoroughness by travelling around Europe to see how the most modern observatories were constructed.

“Neither the Observatory nor the instruments were as good as Augustin stated on the marble tablet”

When Bugge got home, he pulled down the old observatory and built a new one in the shape of an octagonal building with two side wings and provided it with new instruments. Or as it says in a translation of Augustin’s Latin text on the marble tablet, “Supported by the generosity of King Christian VII, Count Otto de Thott took care that this new observatory, after the royal liberality had furnished it with the best instruments, could be inaugurated to Urania on 11 October 1780”.

Amateur Astronomers

Several of the people involved knew each other from the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, where Count Thott (1703-85), who himself was interested in astronomy and had a private observatory behind his Copenhagen palace, was an honorary member.

Thomas Bugge was a regular member just like Augustin, who had studied astronomy in his youth. Later, Augustin delivered a number of talks to the academy, a few of which were published, including one about the difference between the results of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and his French colleague Jean Picard (1620-82). Augustin also made private astronomical observations. After his death, one of his telescopes was thus acquired by Bugge to the Observatory at the Round Tower.

Another Marble Tablet

The sum of good efforts was not enough, though. Neither the Observatory nor the instruments were as good as Augustin stated on the marble tablet, and at some point, perhaps in connection with the closure of the Observatory in 1861, the tablet was taken down and forgotten. Until, that is, it was rediscovered under the organ of the Trinity Church and placed in the Spiral Ramp, although the architect of the tower, Henning Hansen (1880-1945), had advised against it and recommended to include it in the newly founded astronomical historical collection.

The foundation of this collection coincided with the construction of the current public observatory in 1929, and both were commemorated on another tablet that was put up next to the one of Augustin and Wiedewelt. On the new tablet, the reigning king is still mentioned but the principal part is taken by Mayor Ernst Kaper (1874-1940), who also chaired the board of the Round Tower, and the Municipality of Copenhagen, which had just taken over the administration of the tower. And that, in any case, should not be concealed.