This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The Round Tower as a Lighthouse

There is something about the Round Tower and lighthouses. If one starts in the periphery of things that connect them, one can mention that the Round Tower was thoroughly restored in 1870-71 by the architect N. S. Nebelong (1806-71) who covered the majority of its façade with grey cement plaster. A dozen of years prior to this, the same Nebelong had designed a lighthouse close to Denmark’s northernmost city Skagen. The lighthouse reaches a height of 46 metres and was the tallest in Denmark until the lighthouse in Dueodde on the Danish island of Bornholm surpassed it with one metre a hundred years later.

Nebelong’s lighthouse, which was brought into operation in 1858, is built with exposed brick but nevertheless got the nickname The Grey Lighthouse. The name was probably invented so that Nebelong’s lighthouse could be distinguished from an older lighthouse in Skagen – The White Lighthouse – which was built in 1747 by the architect Philip de Lange (c. 1705-66) and whose connection to the Round Tower is more tangible.

Tycho Brahe’s Lighthouse

The history of the lighthouses in Skagen goes back even further. In 1560, King Frederik II (1534-88) decided that three of his fief holders should build lighthouses in Skagen, on the island of Anholt and on the Swedish peninsula Kullen, which was Danish at the time. As it was stated in a royal letter, the reason was that “the seafaring man and foreign skipper” allegedly had complained about running aground when they sailed across the Kattegat and Øresund seas.

In the beginning, they were not lighthouses as we know them, but as early as 1563, Kullen got a brick lighthouse, which was renewed 20 years later by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), who played an indirect role in the construction of the Observatory at the Round Tower. He had been granted the lighthouse in Kullen and the nearby farm Kullagården as fiefs but neglected his duty to light the beacon, and the criticism it provoked, was one of the reasons why he left Denmark.

56 Whale Oil Lamps

The White Lighthouse, which, incidentally, was red to begin with, was the first brick lighthouse in Skagen. Originally it emitted light via an iron basket in which wood or hard coal burned in the same way as one was used to with the previous so-called bascule lights and parrot lights. However, they wanted to try something really cutting-edge with the new lighthouse. An advanced device was therefore produced where 56 whale oil lamps, which were reflected in the same number of polished brass plates, shone through 168 panes of glass. The entire device was about 2-3 metres wide, more or less equally tall and equipped with a gilded sphere on top.

“But lighthouses are not just lighthouses. Over time, Christian symbolism was also attributed to them, which was probably, among other things, inspired by Jesus referring to himself as the light of the world”

The device was made in Copenhagen and before it was shipped to Skagen, it was tested at the Round Tower in March and April 1750. Or in the words of the first of several articles in the newspaper The Danish Post-Gazette of Copenhagen (Kiøbenhavnske Danske Post-Tidender) that covered the story but still had not entirely seized the right number of oil lamps:

“Since it has been held that, instead of the lighthouse in Skagen in Jutland that has so far been in operation at great expense for the common good of the seafarers, it would be more useful and reduce the costs to construct a so-called Pharus or sea-lantern, as has been most humbly reported to His Royal Majesty: Thus, by the Monarch’s most gracious command, such a large lantern, with some thirty lamps, has been completed and today been hoisted to the top of the Round Tower here in the city, in order to test whether it can deliver what is expected.”

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

It is interesting that it was decided to hoist the lantern to the Round Tower’s platform and not transport it by a vehicle when the Spiral Ramp with its even ascending ramp was available. What is even more interesting, however, is the designation the article uses for the sea-lantern, namely “Pharus”.

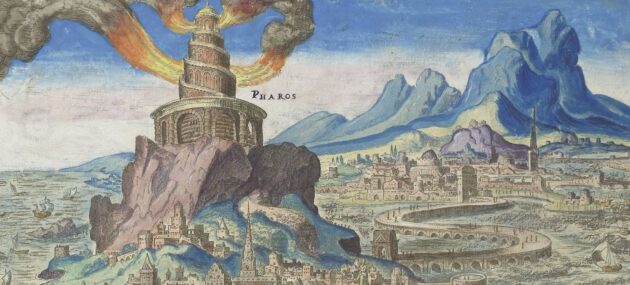

Lighthouses did not come into being with Frederik II’s ordinance in 1560 but go far back in history with one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the lighthouse of Alexandria, as the largest and best known instance. This was built in 279 BC on the island of Pharos, which was connected to the city by a mole, and which not only lend its name to the tower but also became the general designation for lighthouses in several languages, including Latin. On a 1588 map of the area around Kronborg Castle in Elsinore, “Pharus” is thus the term used for the lighthouse in Kullen, and in a Danish-Latin dictionary from 1626 the word is listed as equivalent to the Danish word “Lyctetorn”, meaning lantern tower.

The Light of the World

When the foundation stone of the Round Tower was laid in 1637 there had apparently, for quite some time, been a tradition of depicting lighthouses and especially the famous one of Alexandria with spiral shaped staircases. Something thus indicates that perceptions from the 1500s and 1600s of the lighthouse of Alexandria, which at that time had long since been destroyed by earthquakes, contributed to the Round Tower’s architectural design together with contemporary notions of the Tower of Babel and a host of other sources of inspiration. Perhaps it is even with the lighthouse of Alexandria in mind that the Latin inscription on one of the tables by the Round Tower’s entrance mentions how the Trinity Complex, of which the Round Tower forms part, “competes with the majestic buildings of the ancient world”, as the translation says.

But lighthouses are not just lighthouses. Over time, Christian symbolism was also attributed to them, which was probably, among other things, inspired by Jesus referring to himself as the light of the world in the Gospel of John. This feature of the lighthouses is also connected to the Round Tower since it also functions as a church tower and therefore can be interpreted as a Christian lighthouse.

Much Ado

As to the Round Tower’s specific task of being a test case lighthouse, it only lasted a short while. The lantern for the lighthouse in Skagen apparently got the opportunity to emit light over Copenhagen several evenings in a row, but it was removed after about a month. “Today, the previously mentioned sea-lantern, which has hitherto been installed at the top of the Round Tower here in Copenhagen, has been taken down again”, it says in The Danish Post-Gazette of Copenhagen on April 13, 1750. Later on that same month, the readers get to know that “the frequently mentioned sea-lantern, after it was brought on board, [has been] shipped from here to Skagen so that it can start to operate where it was intended to”.

The latter, however, never happened. Despite the tremendous work effort, the lantern “never got to burn in Skagen”, as one can read in a later description, but was “conveyed back to Copenhagen, probably because, in the meantime, it was discovered that the outer surface of the windows might get covered with ice and snow on winter days, which would cause the due light to disappear under suchlike conditions, or at the least be obscured etc.” What became of the lamp is not known. Whatever the case may be, it did not return to the Round Tower, which had to continue its lighthouse deed on a purely symbolic level.