This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The King’s Heart

There are no limits to the different kinds of utility items that have masked themselves, over time, as the Round Tower. It is possible to find a Christmas tree decoration shaped as the old tower as well as money boxes and candlesticks, and the easily recognisable exterior of the tower has even been borrowed by such diverse things as salt and peppershakers, a children’s book, a stove and an umbrella stand.

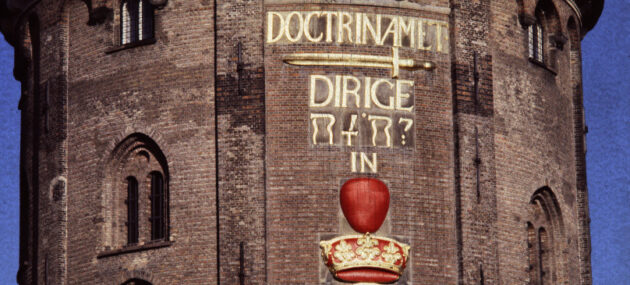

Common to many of these effects is that King Christian IV’s rebus, which shines with a golden glow out towards Copenhagen on the façade above the entrance, is not always depicted accurately. In fact, it is often so poorly copied that it is impossible to read it and even more impossible to understand it.

But the Round Tower would not be the Round Tower without its rebus. It belongs here, for it tells us something important about the Round Tower’s master builder and his idea of, not just the tower, but also the whole Trinity Complex, which the tower is a part of.

The Doctor’s Trine

What the rebus essentially means, is, however, an issue that has been discussed in detail, and even to understand its few elements, which combine words in Latin and Hebrew as well as a picture of a sword and a red heart, has proven to be quite challenging. Ordinary Copenhageners, who have seen the writing high up on the building, have thus made numerous imaginative translations and humorous wordplays thereof. This wide range of interpretations includes the short “Knick-Knacks King Christian number four” and the delightful nonsense sentence, which matches the best of the surrealists’, “The doctor’s Trine with a knife directs squiggle into the heart of Christian IV”.

“Still, not even the linguists have kept away from making suggestions to how the reader-friendliness could be improved”

However, among those who are more skilled in foreign languages there is wide agreement that the text reads, ”Doctrinam et justitiam dirige, Jehova, in Corde coronati regis Christiani Quarti”, which has been translated into, “Lead, God, learning and justice into the heart of the crowned King Christian IV”. Still, not even the linguists have kept away from making suggestions to how the reader-friendliness could be improved.

“The hiero-symbolic inscription that is placed high on the exterior of the tower resembles what one sees in popular picture Bibles, wherein the words found suited are expressed in pictures”, the priest Jacob Nicolai Wilse (1735-1801) thus writes and adds, “However, Doctrinam could also have been expressed by a book, dirige by an arrow, and et by the algebraic +”. After this he concludes that, “Countless people have wondered more about this inscription, than about what is far more puzzling in the clear language, and many peasants have made witchy explanations thereof”.

With the King’s Hand

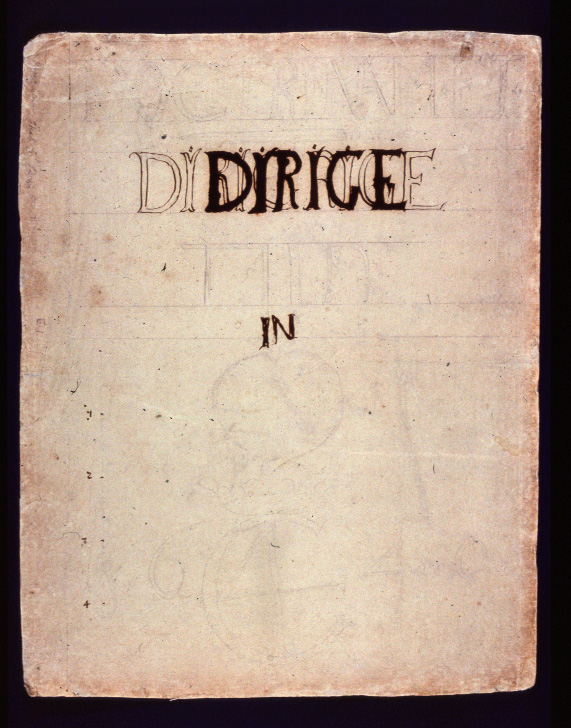

As suggested, peasants were not the only ones tempted to seek explanations. Scholars with a penchant for symbol analysis have been immensely interested too. The philologist and theologist Thomas Bang (1600-61) probably gets the prize for doing the most thorough evaluation. In 1648, a few years after the finishing of the Round Tower, he published an entire book that deals with the gilded inscription, of which there exists a draft written in Christian IV’s own handwriting – although it is often assumed that Thomas Bang assisted him with philological guidance.

The draft is rather preliminary not to say sloppy, especially when it comes to the depiction of the Hebrew signs for Jehovah or Yahweh, but apart from that, it resembles the finished inscription quite well – except from the date that encircles the King’s crowned monogram. On the façade of the Round Tower it says 1642 but when the King made the draft he apparently believed that the tower would be finished earlier and scratched down the year 1640.

Diligent Use of Symbols

It was not the first time Christian IV made use of the elements that are part of the rebus. Tracing examples of this has become a sport among scholars, and the amount that exists is abundant. Christian IV’s own merchandise bearing the elements, for instance, include a gold coin from 1629, a bell from 1636 in Kronborg Castle and an enamelled mirror at Rosenborg Castle.

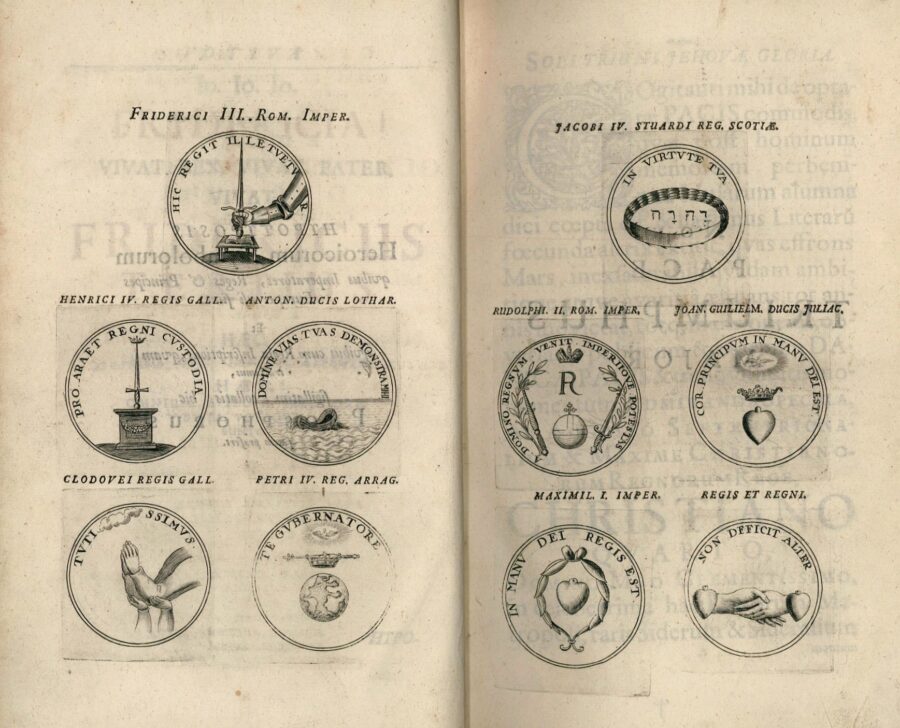

But crowned hearts, swords and Hebrew signs were favoured in other parts of Europe at that time too. Thus, Thomas Bang presents a whole series of princely mottos with related symbols, the so-called emblems, in which the elements of the rebus are used extensively. Early parallels have also been found as far away as in a house in Granada in Southern Spain.

The Right Teachings

The occurrence of analogies abroad should not lead one to believe that the symbolic content is universally the same just because the symbols are. Several of the parallel cases come from Catholic areas, but for Christian IV the main purpose of the enigmatic inscription was actually to point out that he was a monarch with the right Lutheran faith. Even though the Round Tower was built more than a hundred years after the Lutheran Reformation in Denmark, Catholicism was still considered to be a lurking danger, especially during Christian IV’s reign, where the so-called Lutheran Orthodoxy, which involved a very rigorous interpretation of the Lutheran doctrine, was establishing itself firmly.

Bearing this in mind, it makes sense to have a critical look at the translation of the rebus. The Latin word “doctrina” has been translated into “learning” and linked to the library full of scholarly books, which formed part of the Trinity Complex, where Thomas Bang incidentally was the first librarian. But the reason why Christian IV did not choose a book in his inscription, as pastor Wilse suggests, is that this interpretation does not convey the full meaning of the word. For, as Thomas Bang states in his extensive Latin text, “doctrina” must not be understood as learning, but as the right Lutheran teachings, coloured by the Old Testament as they were. It were these teachings that the King imperatively wished to be steered into his heart. That way he could lead the country without it being struck by the wrath of God, which he, as the secular leader of the church, was responsible for.

The Round Tower as Obelisk

It is actually possible to see the Round Tower as an anti-Catholic manifestation in the light of the gilded inscription. Thomas Bang, who was an accomplished Egyptologist, compared the tower with one of the obelisks that the Pope had placed in Rome in the late 1500s, but Bang rejected what he called “the damnable pride of the Egyptian kings”, which was naturally transferred to the Catholic Church’s use of the obelisk, in favour of Christian IV’s “most humble soul devotion”. Similarly, the entire Trinity Complex has been perceived as an “Orthodox Lutheran manifestation in stone”.

Rebuses exist in order to be solved, and there is no shortage of attempts to understand both Christian IV’s rebus, the Round Tower and the whole Trinity Complex. At times, one certainly needs to be wide-awake when the symbol analyses are speeding ahead, as many threads are entangled in the exciting construction. However, evidence suggests that the religious understanding of the rebus is actually one of the most substantial. Regardless if the ordinary Copenhagener actually did understand the intended meaning or just saw stout-hearted squiggle high up there.