This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The King Returns

If one can say that the Round Tower belongs to anyone, then it must belong to King Christian IV (1577-1648). It was he who, as early as February 1637, slightly less than half a year before the foundation stone of the tower was laid, had made an agreement with a citizen in the important Northern German Reformation city of Emden to deliver shiploads of brick for its construction. And it was he who, five years later, in July 1642, sat down at Rosenborg Castle and wrote in a letter that he had drawn a plan of the upper platform of “the tower at Regensen”. The tower, thus, was apparently completed by then but had not yet been named and therefore had to be established by referring to the King’s dormitory building Regensen just opposite the Round Tower.

“There is not a single unequivocal piece of evidence that he drove, rode, let himself be carried, or just walked here”

Christian IV was not slow to acknowledge paternity of the tower on the surface of the building itself. The pious prayer, which shines golden on the facade in the form of a rebus, thus contains his crowned monogram, which is also included several places on Caspar Fincke’s (1584-1655) intricate lattice railing at the top and added in 1643.

The King Takes Care of Everything

The many visitors of the Round Tower are not in doubt either. Countless are the parents and teachers on their way up the narrow Spiral Ramp who, with authority in their voices, have announced to the children entrusted to them that Christian IV drove up here when he was going to gaze at the stars or just look out over the capital city he spent so much energy building and expanding. But in fact, we do not know. There is not a single unequivocal piece of evidence that he drove, rode, let himself be carried, or just walked here. In short: that he ever visited the Round Tower.

Of course, that does not mean that he did not. A source at the time writes of Christian IV that “the King takes care of everything. There is nothing too big or too small that he does not know everything about”, and the King’s letters alone document that he was so actively interested in the construction of the Round Tower and was so familiar with details of the tower’s design that he must have seen it repeatedly. He must have been here.

A Seven-Year-Old Boy

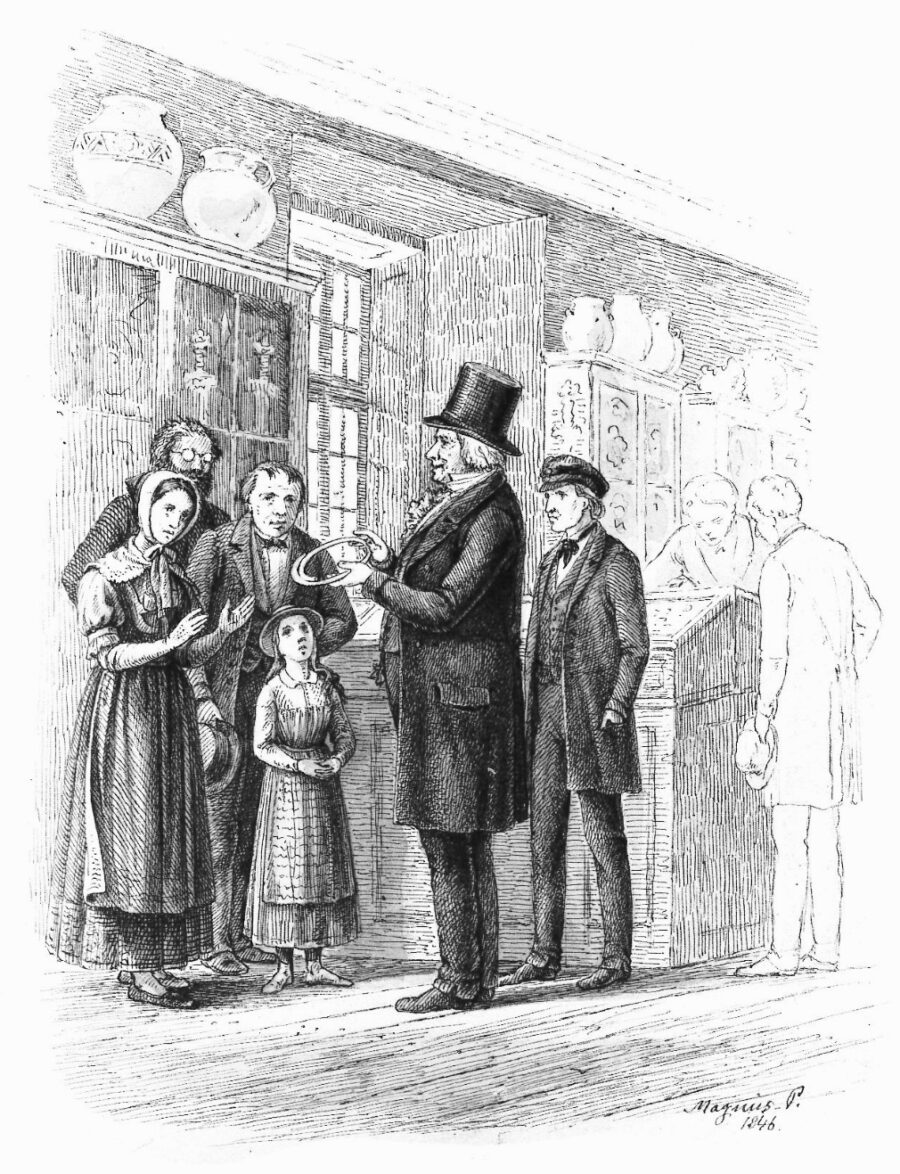

Therefore, in a way we have the right to say that the King returned to the Round Tower in 1819, 177 years after his death. At this time, a number of objects were added to the collection that had been established 10 years earlier in the eastern end of the University Library Hall with access from the tower. Christian IV returned in full figure, elegantly dressed, but in a somewhat younger version than the aging majesty who had built the tower. Namely as a seven-year-old boy on a woven and somewhat faded tapestry. Not yet a fully matured monarch, even though he became the latter just a few years after the portrait was woven.

In 1819, the public was given access to the collection, which later became the National Museum of Denmark, but was formerly known as the Museum of Nordic Antiquities (Oldnordisk Museum). Its prehistoric artefacts have attracted most of the attention because they were the starting point for the museum’s mastermind, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788-1865), and his systematic division of antiquity into three periods of time, i.e. the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. However, there were also things from other eras on display in the Library Hall.

Peculiar Items From Later Eras

In his vision for a new national museum, the initiator of the collection, Rasmus Nyerup (1759-1829), had suggested a classification that was the inspiration of the actual arrangement of the collection’s approximately 6,000 objects. The categories were called “From the pagan age”, “Rune monuments”, “Concerning the Catholic cult in the Nordic countries”, “Concerning chivalry” and “Peculiar items from later eras”. Altogether they spanned a rather lengthy period of time which continued as late as the Renaissance.

Belonging to the latter category, for example – in addition to two pistols that the Swedish King Carl XII (1682-1718) had given to a Norwegian colonel – were one of the masterpieces of the Danish Renaissance known as the Kronborg tapestries. Or rather, what was left of them.

After almost 20 years in power, King Frederik II (1534-88) finally had a son in 1577, who could be chosen as king after him. A few years after the succession was secured, the event was celebrated with the order of no fewer than 40 woven tapestries. They portrayed the King and his chosen son as well as the 99 kings who had preceded them on the Danish throne, beginning with King Dan, who had allegedly given his name to the country.

Royal Applause

The 40 tapestries, which were joined by three additional tapestries with hunting motifs and a woven canopy, were tailor-made for the great hall in Frederick II’s recently finished, magnificent Kronborg Castle, where they were displayed on special occasions, so no one could be in doubt about the antiquity and the continuity of the royal power. The tapestries are considered “the most beautiful and best tapestries that have been produced here in Denmark”, as art historian Francis Beckett (1868-1943) expressed it.

“If they were not available to the public in some way, there cannot have been any reason to mention them in a guidebook for visitors”

Miraculously, the tapestries survived Kronborg’s fire in 1629, after which they have experienced a tumultuous existence with transportation from one royal castle to another, for example to Nyborg Castle. Several of them were lost through time, but almost half were stored in the middle of the 1700s at the royal furniture storage depot in the Prince’s Palace in Copenhagen. Here they remained until 1819, when Lord Chamberlain A. W. Hauch (1755-1838), who was both the head of the furniture depot and chairman of the Royal Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities, the predecessor of the Museum of Nordic Antiquities, proposed that the king surrender them to the museum. A week later, the king welcomed the idea.

Space Shortage

The National Museum’s former director Mouritz Mackeprang (1869-1959), who has carefully studied the history of the Kronborg tapestries, guessed that they were moved directly from one storage depot to another. “At the loft of the Trinity Church, where the museum was located 1807-32, there simply has not been room for them”, he writes.

There must have been some room after all, though. In his guide to Copenhagen museums and collections from 1821, the statistician Frederik Thaarup (1766-1845) thus specifically mentions “Fifteen pieces of tapestry, manufactured for Kronborg Castle during the reign of Frederik II”. If they were not available to the public in some way, there cannot have been any reason to mention them in a guidebook for visitors.

A Quick Decision

But of course, they would not have to have been hung up. Thaarup writes in his directory that objects in the Museum of Nordic Antiquities are kept “in part in large cabinets” and that might have been the case for the tapestries as well. In 1832, the museum moved to Christiansborg Palace because of lack of space, and six years later Christian Jürgensen Thomsen hung them in the new premises and seemed so amazed at how faded they were that he obviously had not been looking at them every day.

He writes in a letter that “when they were hung up, one noticed that they were bleached and what was supposed to be white now appeared soiled”. For that reason, he made a quick decision that all of the walls were to be painted green. That way “the tapestries did not appear dirty, since the colour white was completely avoided in the room”.

Since then, the National Museum has moved again, this time to the Prince’s Palace. In the current museum building, half of the extant tapestries now hang, more or less returning to the space they had while they were in the royal furniture storage depot. The remaining tapestries have come back to their original home, that is to Kronborg Castle. And the King – he also returned to the Round Tower, albeit only for a few years.