This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The Elements of Wind and Weather

Meteorology did not come into being in the Round Tower. As early as 340 BC the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote a treatise about the elements of wind and weather entitled Meteorologica, and at least since then, generation after generation has tried to understand, measure and predict the weather of exactly their location on earth.

“In the 25 years that followed, Horrebow faithfully took readings of his thermometers and barometers and wrote the results into tables”

However, it was in the Round Tower that the systematic collection of meteorological data gathered momentum on Danish soil. It happened from 1751 when the astronomer Peder Horrebow the Younger (1728-1812) began to carry out several daily observations of the temperature and atmospheric pressure as well as of rain, fog, thunder and wind at the top of the tower. This was where the Observatory of the University of Copenhagen was located. Horrebow worked under the leadership of his brother, but apparently, he had taken meteorology, which was regarded as a branch of astronomy, into his own hands and paid for the required equipment himself.

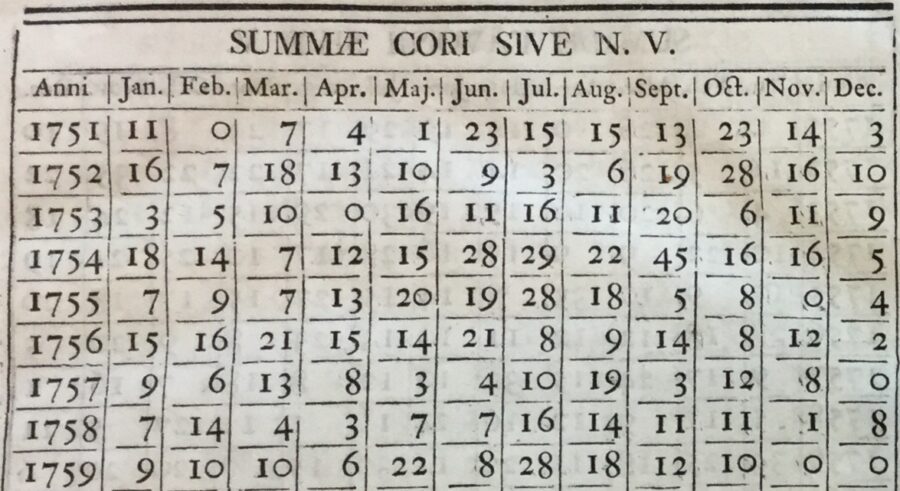

In the 25 years that followed, Horrebow faithfully took readings of his thermometers and barometers and wrote the results into tables, and when he did not become leader of the Observatory as expected after his brother’s death in 1776, he had plenty of time to process the figures, which he published in 1780 in his work Tractatus historico-metereorologicus.

Observations in the Twilight

It was not the first time Copenhagen weather had been measured systematically, but it was the first time the measurements had taken place for such a long period of time. Even though this was a pioneering effort, it was still met with criticism. Two years after the release of Horrebow’s work it was reviewed in the magazine Kiøbenhavnske Nye Efterretninger om lærde Sager and the anonymous reviewer did not mince his words.

“Professor H. has bought his first barometer from a vagrant Italian; with it, he has made observations in the observatory, where it (in his own words) was so dark that he could hardly see the height of the quicksilver,” the reviewer stressed among other things. “These barometrical observations continued to take place in the twilight till 1756, when the observatory was reconstructed and provided with more windows.”

Another point of criticism was that the thermometers were initially located inside, “so that they did not show the temperature of the atmosphere but only the confined air of the observatory”, as stated in the review.

Impossible Observations

However, with time, sentiments more favourably disposed towards at least some of Horrebow’s figures also emerged. This includes Thomas Bugge (1740-1815), who even published several of Horrebow’s results in his own name. As the next director of the Observatory, Bugge continued the meteorological observations. The observations continued until 1819, but the results from some time periods are missing, either because they have disappeared or because it has been impossible to make the observations.

For instance, this seems to have been the case when the Observatory was reconstructed in 1779-80, and it was certainly the case in early September 1807: “In these four days […] no meteorological observations could be carried out,” the original records disclose, “because the city was bombarded by the hostile English siege army”.

A Network of Weather Stations

Still, there was no shortage of results and one may ask oneself what all these figures were good for. Thomas Bugge gives the answer himself.

In a meteorological publication from 1793 he praises an imposing project, which was carried out in these years at the behest of the Prince-Elector of Palatinate. A large number of weather stations across Europe were equipped with similar ultra-modern measuring instruments and send their results to the southern German city of Mannheim where the results were regularly published. In connection to this Bugge writes that, “if meteorologist should ever be able to find out cycles for calculating future weather conditions, there will be no other way than to abstract the general weather rules from this valuable and significant collection”.

“A German astronomer even believed that a time would come when it would be possible to predict rain, snow, thunder and lightning several years into the future”

Hence, the purpose of the many observations was to use them to predict the weather by finding out the regular patterns that were observed in space and by which the weather phenomena were also believed to be moving. A German astronomer even believed that a time would come when it would be possible to predict rain, snow, thunder and lightning several years into the future.

We have not yet reached this point, albeit the diligent observers at the Round Tower did their best to make it happen in the years between 1751 and 1819. The theory of weather patterns is still much debated among meteorologists, but perhaps today, most of us would rather join the less optimistic view of Horrebow’s anonymous reviewer from 1782. In short, he writes that, “Experience has taught us that weather-prophets are generally wrong”.