This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The Development of the Three-Age System

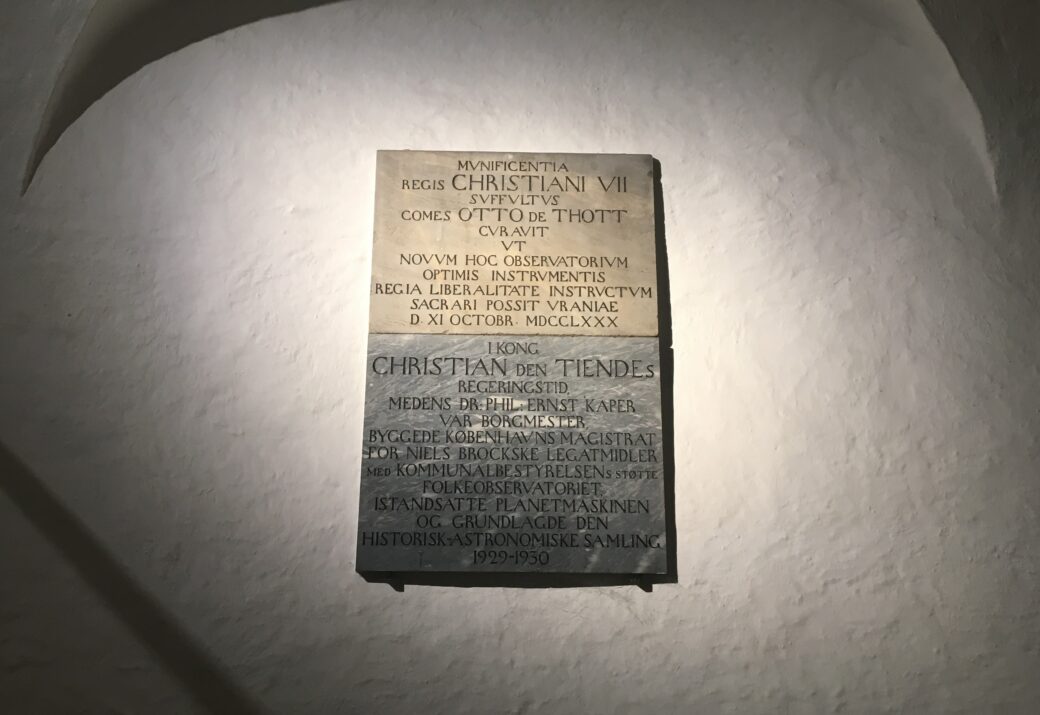

It was not just gold that was gleaming during the Danish Golden Age in the first half of the nineteenth century. More modest materials also got their chance to shine. They constituted the very foundation of the systematic organisation of the past that took place in the 1820s in the Library Hall accessible from the Round Tower. An organisation so precious that it underlies the system still universally used today.

It is the so-called three-age system whereby the human prehistory can be divided into periods named after the material predominantly used for the production of weapons and tools in a given period of time. Stone was used first, then bronze and finally iron. Hence, the Stone Age comes first, then the Bronze Age and finally the Iron Age.

“The transformation happens due to Christian Jürgensen Thomsen”

It was not a new concept that the evolution of mankind had gone through three ages in ancient times and that these ages could be named after materials. Several ancient Greek poets, for instance, make use of the notion of three periods, and in the eighteenth as well as in the nineteenth century, it is used in historical theses. What is new in the Library Hall, however, is that the division becomes more than just a thought and a conception based on old tales. Or as it has been phrased, Denmark’s prehistoric past is being transformed “from literary legend to archaeological reality”.

Endlessly Old

The transformation happens due to Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788-1865), a merchant’s son who in 1816 became responsible for looking after the collection of the prehistoric objects that were located in the University Library on the floor above the Trinity Church. Ten years earlier, the university librarian Rasmus Nyerup (1759-1829) had advocated for the preservation of the ancient monuments of value, and when the prehistoric artefacts were subsequently sent to him from all parts of the country, he installed them in the eastern end of the library.

Nyerup’s dream was that the cultural heritage should be presented in what he was the first to call a “National-Museum” – a term, which for Nyerup also included things from Norway and other areas that were or had been under Danish rule. Based on written testimonies from the library’s books, he therefore published a detailed proposal for how a number of objects and monuments, in practice often copies or reproductions of the originals, should be divided between four rooms – two of them containing “Prehistoric Heathen Monuments” and two containing rune stones and medieval monuments respectively.

The dating of the latter being more or less certain, Nyerup was on shaky ground when it came to the three remaining rooms and the two first ones in particular. “Everything that has its origin from an age that precedes the establishment of the Christian faith in these countries, can rightly be termed endlessly old”, he thus writes and continues, “We know it is older than Christianity, but whether it is a few years or a few hundred years – indeed, perhaps more than a thousand years – older, is almost nothing but sheer conjectures and at most only plausible hypotheses”.

A Collection in Chaos

The idea of an institution that could ensure the vanishing cultural heritage was quickly officially acknowledged and in 1807 the Danish Royal Commission for the Collection and Preservation of Antiquities was established, which is considered the beginning of the current National Museum. Nyerup initially worked as the commission’s secretary himself but it was not before the position was handed over to Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, that things really started to happen.

At the time when Thomsen took over, there was little control over the collection. “In dust, desultory disorder, hidden in drawers, hooks, scarves, papers, it was all one big chaos to me”, he thus writes to the historian Lauritz Schebye Vedel Simonsen (1780-1858), who was a member of the Antiquities Commission. Little by little, however, the new secretary managed to organise the collection and thus became closely familiar with the objects, which was a prerequisite for the development of the three-age system.

All the objects were studied empirically together with the information about where they had been found and what other objects they were found together with. “You will easily understand,” Thomsen continues to write to Vedel Simonsen, “that since I have had every single piece the commission owns, not just one but many times in my hands, there is probably no one who knows what the collection contains as well as I do”.

Journeymen and School Children

It is uncertain when Christian Jürgensen Thomsen’s theory of the tripartition was so complete that he could begin to talk about it during his famous tours of the collection, and neither do we know for sure when he started organising the objects according to the new principles. Both probably happened gradually, but when the British tourist Miss Frances Williams Wynn visited the Round Tower in 1827, the presentation of the collection, which Thomsen gave her, left no doubt about the order of the objects.

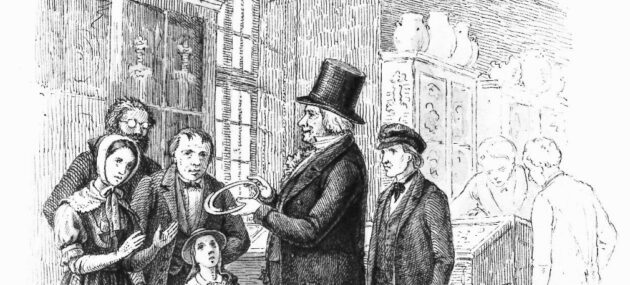

The three-age system does not, however, gain full acceptance as a principle of classification until the collection is rearranged in the mid-1830s. At that time, the museum has been relocated from the University Library to Christiansborg Palace, partly because it has simply become too popular. Guests “from the city, the countryside and abroad, including dozens of journeymen and schoolchildren” disturb the library users, one complaint states in 1832 – and besides, the ancient relics take up too much space as many of the books “have to be stored in double rows,” it says.

More Than a Presumption

It is also during the time when the museum is housed in Christiansborg Castle that Christian Jürgensen Thomsen formulates his theory in print for the first time. It happens in the book Guideline to Scandinavian Antiquity (Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed) from 1836, where he gives an overview of monuments and antiquities from the Nordic past and in doing so includes a few pages about how old the objects are in relation to each other. “In order to facilitate the overview, we will give the different periods, whose boundaries could not be accurately defined, separate names”, he writes. The names are the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Thomsen was still careful to point out the exact time frames of the three periods, and in general, he believed that the theory of the three periods needed to be studied more thoroughly before it could become more than just a presumption. Already, however, it was way past Nyerup’s sheer conjectures. And such a breakthrough is certainly worthy of a Golden Age.