This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Behind Protective Walls

Most people are familiar with a fireproof dish. What is more unusual is to talk about a “fireproof house”. It is, nevertheless, what the Round Tower has been called. And rightly so, since its robust walls have offered protection for centuries to Copenhageners who sought shelter from fire and bombs.

Many of the latter were dropped during World War II. Thus, when Denmark was occupied in 1940, the question of how to provide protection for the people during the Allied air raids quickly arose. In Copenhagen, dugouts and air raid shelters started being built and arranged in parks, green spaces and other available places, for the ambition was that everyone should be able to reach safety in less than three minutes. In Tivoli alone, shelters were built for 20,000 people. In other parts of the city existing localities were fitted out for the purpose – for instance the lower part of the Round Tower, which could be turned into a shelter with sandbags, benches adjusted to the sloping floor and room for 600.

As mentioned before, it was not the first time the solid tower was chosen to protect the Copenhageners when they were in danger. A 1.60 m thick outer wall made of stone is, after all, more than most people had at their disposal. Thus, it is conceivable that the Spiral Samp was already used as a refuge, at the time when the city was bombarded during the Swedish siege from 1658-60, and again in 1700, when an enemy fleet with ships from England, Holland and Sweden fired cannonballs over the city in the beginning of the Great Northern War.

Huddled Furniture

However, as far as is known, there exists no verified information about the Round Tower being used as a shelter before the fire of Copenhagen in 1728, during which the Spiral Ramp was filled up with a stream of people and those belongings that they had managed to rescue from their far less fireproof houses.

“Strangers took up all the space with their household effects in the tower’s passageway below me”, the astronomer Peder Nielsen Horrebow (1679-1764) thus recounts. He and his eldest son had taken shelter in the rooms below the Observatory at the top of the Round Tower after his home had gone up in flames the previous day. But when the fire reached the Trinity Complex as well, where it destroyed the upper part of the tower, Horrebow and his son had to find a way to get down to the street, “which they did not reach until they had laboriously climbed over mountains of huddled furniture”, as it says in a description.

“It must have been an inferno of heat, smoke and panic both inside and outside the Spiral Ramp”

It must have been an inferno of heat, smoke and panic both inside and outside the Spiral Ramp, for the fire also reached the University Library, whose entrance was located inside the Round Tower. The library above the Trinity Church, as well as big parts of the church itself, were destroyed by the fire. A poem written in the time after the fire thus offers a vivid snapshot of how bad it was. “On the Round Tower it is neither possible to see the Sun nor the Moon,” the poem states, “and the star’s path is clouded by fog and flames; / the fire star flares in every corner and nook / and it is awful to see around in Aabenraa [a street close to the Round Tower].”

More Huddled Furniture

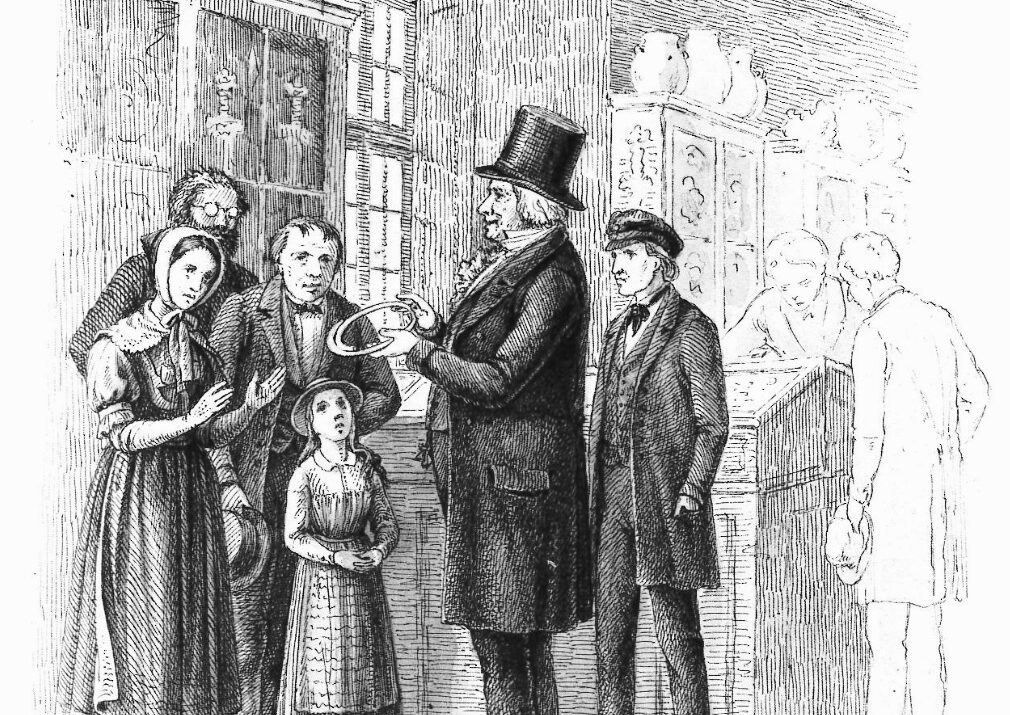

The Round Tower itself, however, did more or less make it through the great fire and was again able to function as a shelter for the Copenhageners in 1807, when the British bombarded the city three September nights in a row. According to a description made by Christian Ludvig Strøm (1771-1859), who was the son-in-law of the university librarian Rasmus Nyerup (1759-1829), the situation in the Spiral Ramp gradually came to resemble the one in 1728. Nyerup was also the head of the old dormitory Regensen, which is located across the street from the Round Tower, where he and his family therefore lived.

“When the bombardment began shortly after, Nyerup made his way to his post in the University Library”, the son-in-law recounts. “The rest of us went along and camped in the tower’s passageway outside of the library. We thought this to be safer than Regensen, where a grenade killed a servant on the first day and bombs destroyed several rooms in the days that followed. Other people from the city must have had the same idea. On the first night we were probably the only ones there, but the next day a few other families began to arrive, and on the third day the entire passageway was filled from top to bottom with household effects, beds and people. During this huddle, different incidents took place that would have caused a lot of fun under normal circumstances but now they only elicited a brief smile.”

Shattered Limbs

The Round Tower and the Trinity Church both suffered much less damage in 1807 than they did in the fire almost 80 years previously. But the people of Copenhagen were not so fortunate. The medical student Oluf Lundt Bang (1788-1877), who later became a celebrity doctor and, amongst others, treated the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-55), has depicted the suffering in his versified memoirs, but also the security that the Round Tower’s thick walls were able to offer to the victims of the bombardments:

“Among all the places that provided protection,

one thought that the Round Tower was the safest,

half a hundred families

therefore lived along its spiral ramp.

A screen, sometimes not even that,

separated them from each other,

and no difference was made

with respect to money and rank.

There I visited and provided help to

neighbours from Kannikestræde [another street close to the Round Tower],

who had been badly injured by the bombs,

in the basement where they had sought shelter.

One daughter got her foot shot off,

two others got even more wounds,

now they have moved to the Round Tower

and will have to be cured by me.

The shattered limbs, the wailing people,

the burning houses in the city

soon depressed my merry disposition,

I understood the shame and damage.”

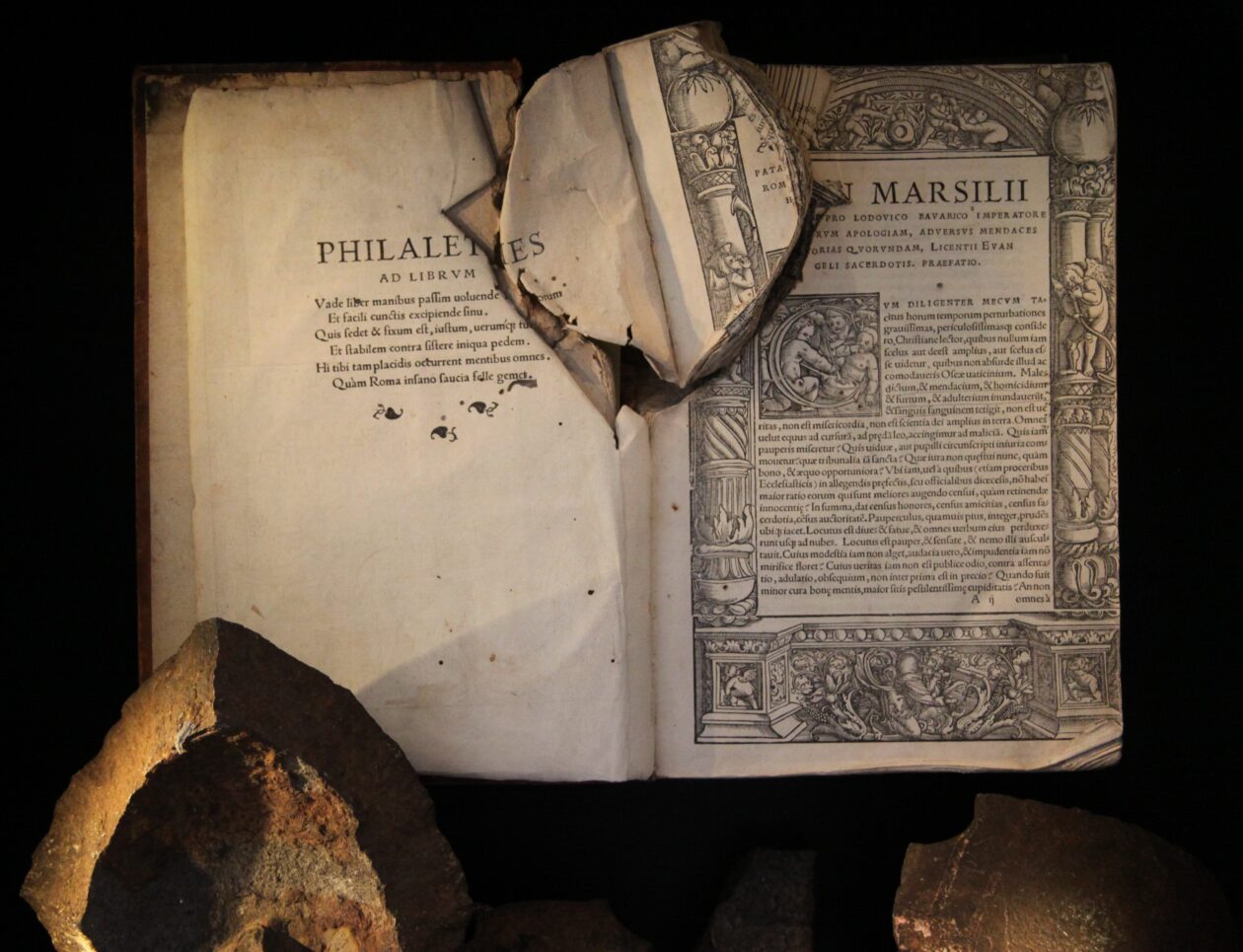

Most of the book stock, which had managed to be re-established in the University Library after the fire in 1728, also found safety behind the protective walls. The manuscripts had been successfully hidden in the basement before it was too late while the most precious books were thrown into the Round Tower’s hollow core. Famous for being an exception, is the only book that, according to tradition, was damaged. Ironically, it is a copy of Marsilius of Padua’s medieval text Defensor pacis (The Defender of Peace). It is now on display in the Library Hall as the only visible trace of the anguish that the Round Tower has also witnessed.