This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

The Summit that Never Took Place

Among the list of Danish kings the nickname “the People’s King” is usually reserved for Frederik VII (1808-63) who had the royal motto “The people’s love, my strength” and who, a few months after his accession to the throne in 1848, renounced absolutism and instead became the leader of a constitutional monarchy.

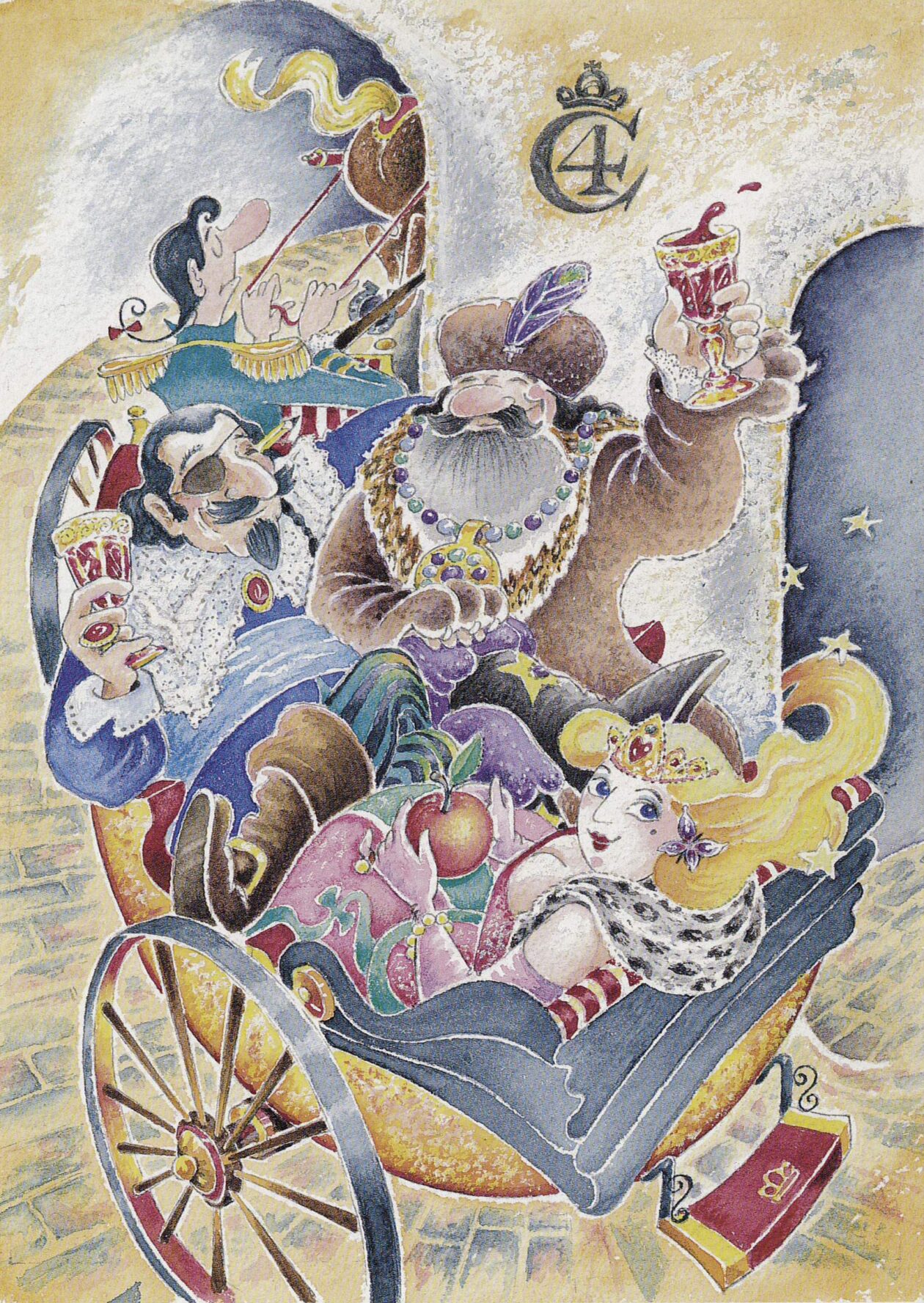

If one is to believe a story that was also told during Frederik VII’s reign, there was, however, another “People’s King” called Frederik. The story unfolds in the Round Tower and one of its leading characters is Frederik VII’s namesake, the absolute King Frederik IV (1671-1730). The other prominent figure of the story is the Russian Tsar, Peter the Great (1672-1725), who visited the Round Tower several times during October 1716. His first visit occurred, by all accounts, on October 1st, where he climbed the tower’s Spiral Ramp on horseback whilst his wife followed in a horse-drawn carriage.

In the Bosom of the People

The newspaper The Copenhagen Post-Rider (Den Kiøbenhavnske Post-Rytter) is the most credible source for this visit. It relates that the Tsar and Tsarina’s day continued at Rosenborg Castle, “where they were gloriously entertained by Their Royal Majesties and after the royal banquet amused themselves with tilting at the ring on Rosenborg’s water canal”.

In other accounts of the visit, one reads that the Tsar shared a dinghy with the Danish Queen during what is also known as “a carousel on water” whilst Frederik IV shared one with the Tsarina. Supposedly, it was a delightful sight to look at the grand royals amuse themselves in the gilded boats that reflected the light flames of the torches.

“The story fits well into the national romantic narrative of the time, since one could mirror the incumbent People’s King Frederik in the myth of a no less beloved predecessor as the guarantor of national cohesion”

It is unlikely that the King and Queen have been present at the Round Tower while the Tsar and Tsarina were there, mostly due to the fact that the Post-Rider only mentions them later on in that day’s program. Still, posterity has placed Frederik IV at the top of the tower in the scene with the Tsar that serves to expose the differences between the two monarchs. In Hans Christian Andersen’s (1805-75) novel To Be, or Not To Be (At være eller ikke være) from 1857, the scene is described as follows:

”Within the tower there is no ascent by steps, the top is reached by a winding stone passage, so smooth and gradual in its upward progress that the Russian Tsar, Peter the Great, once drove up, it is said, all the way to the top in a carriage drawn by four horses. When he reached it, he commanded one of his attendants to throw himself over, and the man would have done so, had he not been prevented by the Danish King. ‘Would your people be so obedient?’ asked the Tsar. ‘I would not give such a command!’ replied the King. ‘But I know, in regard to my subjects, even the poorest among them, that I might lay my head on his lap, and sleep in safety!’”

The King Narrates

The story fits well into the national romantic narrative of the time, since one could mirror the incumbent People’s King Frederik in the myth of a no less beloved predecessor as the guarantor of national cohesion. However, even though Hans Christian Andersen puts a national romantic tale into words, he also underlines that we are dealing with a myth. “Such is the legend and, to us Danes, it is a very beautiful invention”, he thus writes in the paragraph that follows the story.

Hans Christian Andersen is not the first to mention the alleged incident at the Round Tower. In the writings of another great poet from the 1800s, N. F. S. Grundtvig (1783-1872), the scene also comes to life. Grundtvig reworked and enlarged the medieval Rhymed Chronicle (Rimkrønike), wherein the kings of Denmark tell the story of their lives. To Grundtvig, the Rhymed Chronicle was his “life’s book, which I, honestly, have read much more often and know much better than my Bible”, and in his extended version he lets Frederik IV narrate the story himself.

Cognate Ideas

Grundtvig published some examples of how his Rhymed Chronicle should look like in 1834, that is, almost 25 years before Hans Christian Andersen’s novel. However, in these examples he jumps directly from Frederik III (1609-70) to Christian VII (1749-1808) and hence does not mention Frederik IV, who was only included when Grundtvig’s son published the entire extended version of the Rhymed Chronicle in 1885, after the death of his father.

Hans Christian Andersen is one of the first to publish the monarchs’ word-duel at the Round Tower, even though cognate ideas already existed long before. When the historian Niels Ditlev Riegels (1755-1802) published the first volume of his Outline of the History of Frederik IV according to Høier (Udkast til Fierde Friderichs Historie efter Høier) in 1795, he thus made a pungent juxtaposition of Frederik IV and Peter the Great’s view of humanity, and from this point on there was only a short distance to an actual dramatization of the contradistinction.

“Friderich did not have the same low opinion of human worth as Peter the Tsar,” Riegels writes, “he did not consider his subjects as flies whose life relied on the king’s caprices, whose fate depended on whether he wanted to crush one or several thousand of them with his own hand”.

The King Omitted

The meeting between the King and the Tsar at the Round Tower has ostensibly been told by generations of schoolteachers, who, quite literally, have thus given Peter the Great’s spectacular visit on horseback an ideological superstructure. However, not everyone has used the visit to glorify the Danish King. The author Vilhelm Bergsøe (1835-1911) relates the first part of the story in his novel From the Old Factory (Fra den gamle Fabrik) from 1869 and completely omits the popular King in his version of it.

“I knew that Peter the Great had descended the spiral ramp with four horses”, Bergsøe writes, “after he in jest had ordered one of his footmen to jump over the platform on top”.

As regards the Tsar’s means of transport and the number of horses, Bergsøe has as free an approach to reality as Hans Christian Andersen. But who has ever demanded that a myth should stick to particulars?